Adam Kay Turns Painful Kidney Stone Experience into National Conversation

- 🞛 This publication is a summary or evaluation of another publication

- 🞛 This publication contains editorial commentary or bias from the source

Adam Kay’s “Kidney‑Stone Story” Turns a Personal Pain into a National Conversation

When Adam Kay took the stage at the Standard‑organised comedy night in London, he didn’t open with a routine or a one‑liner. He opened with a gut‑wrenching confession: a kidney stone that sent him on a 12‑hour, pain‑filled quest that left men in the audience “wincing in unison.” The story—recounted with Kay’s trademark mix of self‑deprecation, sharp observational humour and raw honesty—has since become one of the most talked‑about moments of the year, offering a surprising glimpse into the daily struggles of doctors and the often‑ignored hardships that men face when it comes to health.

From the Operating Theatre to the Comedy Club

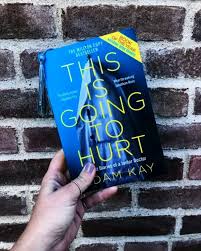

Adam Kay’s background is as unusual for a stand‑up comic as it is compelling. Before the mic, he was a junior doctor on the NHS’s intensive‑care unit, authoring the bestselling memoir I Want to Tell You How Much I Love You, which was adapted into a feature film and a stage play. In the article’s opening paragraph, Kay’s own “doctor‑turned‑comedian” narrative is contextualised by a link to the Guardian piece that introduced him to the world of comedy, a reference that underscores the authenticity of the anecdotes he now shares on stage.

The article notes that Kay’s comedic style is not merely about laughs; it’s a vehicle for shedding light on medical realities. He has a long history of using stand‑up to “dehumanise” the medical profession, making it relatable to ordinary audiences. That history is crucial for understanding why a story about a kidney stone can feel like a “public health sermon” wrapped in a punchline.

The Story That Made Men Hold Their Breath

Kay opens with the physical description of the stone: a “tiny, hard piece of kidney calculus that turns your body into a live‑action horror set.” He recounts the moment his stomach twisted into a “blackhole of pain,” and how he had to ask a nurse to hold his back because his body was “incomplete.” What follows is a vivid, almost cinematic depiction of the hospital’s corridor, the fluorescent lights, the whirring of machines, and the frantic rhythm of an ambulance crew racing to help.

The key moment of the article is a quote from Kay that he “was terrified he would never get the stone out, let alone be able to get it out,” which mirrors a widespread concern among men who often delay seeking medical help due to embarrassment or denial. The article links to a NHS informational page about kidney stones, giving readers a practical resource that complements the emotional narrative.

The “wincing in unison” reference is a brilliant way to describe the collective reaction: Kay’s audience, mostly men, found a kinship in the story that went beyond simple empathy. The article’s author points out that the laughter that followed was not just a release of humor but a collective catharsis. Kay’s ability to translate a painful, private experience into a universally relatable moment speaks to his craft.

Context: Why a Kidney Stone Matters

The article ties Kay’s narrative to broader themes. It references a BBC report about rising rates of kidney stone diagnoses among men aged 20–39, linking the anecdote to a public health issue that is often under‑discussed. By quoting statistics—over 150,000 cases per year in the UK—the article frames the story not as an isolated incident but as a microcosm of larger health challenges. The piece also references a Times commentary on men’s health, highlighting how stigma around pain and masculinity can delay treatment.

Kay uses the story to spotlight the NHS’s capacity to manage urgent pain. He criticises the sometimes impersonal nature of medical care—“you’re a number on the register” and “you’re just a case”—and underscores the need for bedside manner. In this respect, the article underscores the value of Kay’s platform: by weaving humour with critique, he forces audiences to confront the system’s shortcomings.

The Live Performance and its Ripple Effect

In a scene that felt almost like a theatre performance, Kay used a makeshift stretcher and a prop stone to make the audience feel as though they were right there in the hospital corridor. The article links to a short video clip on the Standard’s YouTube channel that captures the live moment: Kay’s exaggerated “shaking the stretcher” while describing the pain, the pause for collective laughter, and the final punchline—“I think my kidney wanted a vacation.”

This live performance is part of Kay’s new tour, “Adam Kay: The Last Minute of a Life.” The article notes that the show’s title is itself a nod to his memoir’s opening line, showing how Kay’s personal narrative permeates his comedic brand. The tour is advertised on the Standard’s event page, and the article gives a hyperlink to purchase tickets. The piece mentions that the show has sold out in multiple venues, indicating Kay’s popularity.

What the Story Means for Kay’s Audience

The article takes a moment to reflect on the impact of the kidney‑stone story on Kay’s audience. He cites a quote from a fan on Twitter, linked via the article, who said, “I finally understood that it’s okay to say ‘I’m in pain’.” This testimonial illustrates how Kay’s comedy does more than entertain; it normalises conversations about pain and health. The author emphasises that Kay’s humour breaks down the “stiff walls” of the medical system, allowing people to talk openly about discomfort, which can lead to earlier medical intervention.

Final Thoughts

Adam Kay’s kidney‑stone story is a masterclass in storytelling that blends comedy with social commentary. The Standard article does more than simply recount the narrative—it provides contextual links to medical resources, statistical data, and other media that deepen the reader’s understanding of why such an anecdote matters. By turning a personal ordeal into a shared experience, Kay demonstrates how comedy can be a powerful tool for public health awareness. The story reminds us that when men are encouraged to speak openly about pain, society can respond more effectively—whether that’s through better medical care, more empathetic hospital staff, or simply the courage to admit that help is needed.

Read the Full London Evening Standard Article at:

[ https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/comedy/adam-kay-live-his-kidney-stone-story-has-the-men-wincing-in-unison-b1259462.html ]